22 December 2023

Summary 2023

Let us tell you what we remember about the past year 2023 - Neural networks, electronic subpoenas, more leaks, and severe laws. We have organized all the events into cells and in each cell we will highlight key developments in digital rights. Sometimes it’s good news, sometimes it’s not so good news, but it’s important to continue the fight together to do more good in this world.

Video (rus): Summary 2023 by Roskomsvoboda

January

Neural networks went mainstream

“Hello, ChatGPT, let’s get a degree together”. A student at the Russian State University for the Humanities (RSUH) successfully defended his thesis written with the help of the neural network powered, ChatGPT. Whilst the university was embroiled in scandal, the State Duma turned to the guy for help. The RSUH leadership called for restricting access to the chatbot in educational institutions. Meanwhile, the student was invited to the State Duma Committee on Information Policy to participate in discussions on the use of AI in education.

Over the course of the year, interest in ChatGPT and other neural networks grew tenfold. If Russians searched Yandex for the term “ChatGPT” 10,000 times in January, by November it had grown to 490,000 times (according to Yandex Wordstat data). Russian companies launched their own neural networks, and universities changed their rhetoric from one of prohibition to acceptance. Moscow City University, for instance, allowed students to use neural networks in writing their finals papers.

Whilst questions surrounding the ethics of using neural networks and their legal status persist, it was in January 2023 that their active integration into people’s daily routines truly began. Meanwhile, throughout the year, IT giants continued competing for the title of developer of the smartest AI solution.

Crackdown on LGBT

At the beginning of the year, authorities declared a crackdown on LGBT propaganda (the law prohibiting its distribution among minors came into force in December 2022). Publishers and streaming services were the first to come under close scrutiny from the authorities.

In January, the first administrative case under this article was initiated against Popcorn Books, following a tip off from State Duma deputy Hinshstein. Despite this, the publishing house didn’t change the covers of the “LGBT” novels listed on their website and even added a link to an article of the Russian Constitution stating, “Freedom of mass information is guaranteed. Censorship is prohibited”.

Later, fines rained down upon online cinemas for incorrect age ratings on movies depicting LGBT scenes. By the end of November, the fines amounted to 29 million rubles, and the total number of cases filed under the new article reached 117 (according to Mediazona). On November 30, the “International LGBT Movement”, which formally doesn’t even exist, was declared an extremist organization in Russia.

January 28 – Data Protection Day

Data Protection Day also takes place in January. On this day, the annual Privacy Day conference takes place, gathering international experts to discuss key issues and matters in this field. The Privacy Day conference will be taking place again in 2024. A little spoiler: we’ll be discussing the topic of neural networks, among other things. Stay tuned for announcements! To see how events have unfolded both in 2023 and prior, check out the YouTube channel.

What happened next

February

The year of wartime blockings

In February 2023, the number of Internet resources blocked by Russian authorities for reasons of wartime censorship exceeded 10,000. Among the first to be blocked were social networks (Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and Facebook Messenger), alongside hundreds of independent media outlets like Meduza (which has been classified as an “undesirable” organization since January 21, 2023), Mediazona, BBC, DW, Radio Liberty, Republic, 7X7. Horizontal Russia, The Village, Taiga.Info, Echo of the Caucasus, Paper – some of which have been subsequently forced to close. Several sites were even added to the banned register twice on the basis of separate decisions.

According to Russian authorities, services like Patreon and Grammarly, the job search site Jooble, the visual arts online encyclopedia WikiArt, the online game S.T.A.L.K.E.R. 2, and SoundCloud, are also involved in the dissemination of discrediting materials and fakes about the Russian army.

The primary censors in this case remain the Prosecutor General’s Office and the “Unknown government agency”, which, according to many indications, is closely linked to the Prosecutor General’s Office.

In 2023, the blockings also extended beyond Russia, with the websites of three US government agencies, as well as dozens of Ukrainian sites, foreign media outlets, and even online stores and pirating sites all being hit with the ban.

**By November 2023, the number of resources blocked due to wartime censorship surpassed 15,000. Here is who was affected. **

A study by Roskomsvoboda and the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) found that not all domains blocked under wartime censorship have been entered into Roskomnadzor’s register, and different ISPs use different censorship methods (e.g. DNS, https, TCP, etc) when blocking. These and other blocked sites remain accessible in Russia via VPN, despite the authorities’ repeated attempts to ban them too.

“Foreign agents” at the ECHR

February also brought with it some positive news. For instance, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) began considering 42 complaints brought forward by Russian individuals and organizations formally recognized as “foreign agents” – like the Institute of Law and Public Policy, The Association of Russian Carriers, The Andrey Rylkov Foundation, the Centre for the Protection of Mass Media Rights, Yekaterinburg Memorial, the League of Votes, LGBT organization Phoenix Plus, the Nasiliu.net (No To Violence) center, the April project, the Svecha (Candle) Foundation, as well as civil activists. Although Russia may refuse to comply with the ECHR’s ruling, the court has the right to recognize that the “foreign agent” law violates the rights and freedoms of Russian citizens. In April, the ECHR commenced work on the first “discreditation” cases, but their outcome remains unknown. On March 15, 2022, Russia withdrew from the Council of Europe and refused to comply with the ECHR judgements issued after this date.

What happened next

March

Discreditation and more discreditation

If March 2023 could be described using a single adjective, it would be “discrediting”. The cost of speaking out about the “special operation” was already hovering at around 30,000 rubles per social media post, but from March onwards, it increased even further. During this month, a law pertaining to criminal liability of up to 15 years for discrediting any participants of the “special operation” was speedily introduced, approved, and signed by Putin. While previously the main danger lay in speaking critically about the Russian Armed Forces, the new law also prohibited discussions about voluntary formations, as well as organizations and individuals who “assist in fulfilling tasks assigned to the Russian army”. Punishments for speaking freely on this topic were set at 5 million rubles, up to 5 years of forced labor, or imprisonment for up to 15 years.

There have been some high-profile verdicts: Dmitry Ivanov, a former math student and creator of the Telegram channel “Protest MSU”, who received an 8.5-year prison sentence for “spreading false information” about the Russian army; and Alexei Moskalyov who was sentenced to 2 years in prison for social media posts and drawings produced by his 13-year-old daughter, which one of her teachers had complained about. This is the case in which the girl was initially sent to an orphanage, whilst the father fled prior to a verdict being reached, before eventually being caught in Belarus and extradited.

A total of 8055 administrative cases have been filed under the “discreditation” article since the start of the “special operation” (according to data provided by Mediazona as of October 2023). Roskomsvoboda and OVD-Info calculated that at least 2,000 of these cases mention social networks. With regards to criminal cases, in the first half of 2023, 21 people were convicted for spreading “fakes” (8 sentenced to restrictions on freedom) and another 14 convicted on “discreditation” charges (with 2 receiving prison sentences).

Leaks and more leaks

March also brought us several major data leaks – with 55 million lines of personal data leaking from “SberSpasibo” and HSE University succumbing to a leak containing scans of students’ passports, lists of employees exempt from military service, and other sensitive information. In just the first three months of 2023, 27 leaks were identified in the country, resulting in 165 million records on Russian citizens being exposed to the public. Guidelines on how to protect your data from leaks and sleep peacefully at night are provided by Securno.

What happened next

April

Electronic Summons

By April, officials authorized military recruitment offices to issue digital summons for army service. It came into law that same month, immediately after being signed and approved by the President, thereby marking the launch of two new registers on military service registration and summonses. Upon receiving a summons through any means, including electronically, leaving the country is prohibited. Furthermore, an individual dealt a summons must report to the military recruitment office within 20 days, or else face the prospect of losing the right to work as an individual entrepreneur or be self-employed, receive loans, and even register real estate or motor vehicles. Information about this “happy letter” can be found in the register itself, on Gosuslugi or when visiting a Multifunctional Centre for the Provisions of State and Municipal Services (MFC).

The register of military registration went into test mode on October 1, 2023, but full functionality won’t be achieved before 2025. The Ministry of Digital Development claimed that the register would start operating in one or two Russian regions by the end of this year. Given that there has been no word yet about the launch, there are two possibilities: they missed the deadlines or simply launched it without telling anyone.

The register now collects, among other things, data on health and marital status, education, employment (and the employer), as well as official place of residence and actual place of residence. The fulfillment of the latter, at least in Moscow, is aided by the use of facial recognition technology, which has been repeatedly noted for human rights violations in the past.

Laws, Ideas, Repression

Overall, April was quite an active month, especially with regards to the already repressive legislative landscape. Life imprisonment was approved for treason, the loss of acquired citizenship imposed for “discrediting” the army, and criminal sentences handed out for assisting international bodies whose decisions contradict those made by Russia. The latter law, which provides for up to 5 years in prison, is linked by many media outlets and opposition politicians to the issuance of an arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin by the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague.

They didn’t forget about technology either: Roskomnadzor announced its intention to employ neural networks to combat fakes, and the Ministry of Finance spoke once again about cryptocurrencies and the imminent creation of an experimental special committee.

What happened next

May

The Internet – A Threat to Children

In May, Putin signed an executive order on the “Comprehensive Child Safety Strategy of the Russian Federation until 2030”, where some interesting turns of phrase, like “preserving children”, “external ideological-value expansion”, and, of course, “threats to safety in the informational space” were used. Yes, authorities deemed the Internet to be one of the main threats to children, stating that the online environment “contributes to the rise of mental illnesses, destroys established moral norms”, and, just generally, “causes moral harm”.

What surprises the officials have in store for the implementation of this strategy will only be revealed next year – the planning stage will continue until 2024, with actual measures coming into effect from 2024 to 2030.

In the same month, the Concept of Information Security for Children was approved. This document also highlights the importance of “traditional values” and protection from online threats.

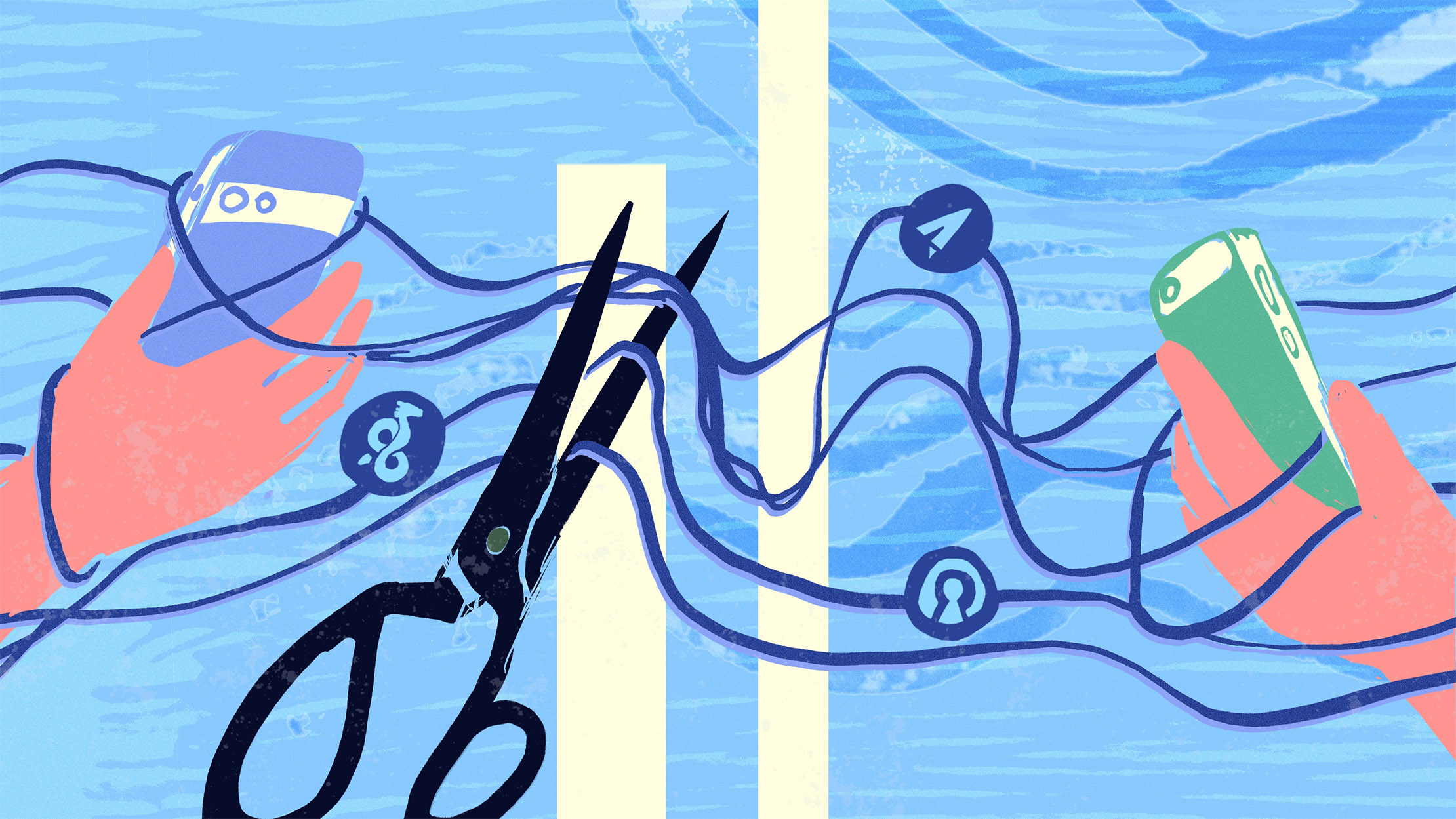

Blocking of VPN services and protocols

By the end of 2022, Russia had the highest adoption rate of VPN technologies. In 2023, the number of VPN-users among Russians increased by a further 37%.

Simultaneously, VPN censorship in the country is also gaining momentum. Blockings are affecting not only specific services but also VPN protocols, like the popular Shadowsocks, WireGuard and OpenVPN. At the end of May, OpenVPN was blocked by several Russian providers, which is attributed to equipment checks on internet censorship systems. Mass service disruptions reoccurred in August but were also recorded across different regions and providers throughout the year.

By the fall, authorities concluded that merely blocking VPNs was insufficient and decided to block information about them as well: how VPN services work, how to install them, and other ways to evade Internet censorship. Initially, the task was to be undertaken by Roskomnadzor, as was stated in the Ministry of Digital Development’s document, but later, the Prosecutor General’s Office also took on this responsibility (with the State Duma approving the bill on this matter in October 2023). It’s anticipated that blockings won’t be limited to websites with links to download VPNs, but also resources that simply discuss the benefits of bypassing blockings.

Currently, the domains of 8 out of the 15 most popular VPN services are already blocked on the territory of the Russian Federation (according to Roskomsvoboda’s research data). This means that we’re approaching a situation where to download a VPN, you’d need to have another VPN already installed. By the way, you can choose and download a service for yourself on the VPNlove.me marketplace (it will allow you to use a Russian bank card to pay for the subscription).

What happened next

June

Undesirables are all around

In 2023, alongside “foreign agents”, the practice of designating organizations as “undesirable” intensified in Russia. In June, the Prosecutor General’s Office assigned this status to the international human rights group Agora and the American structure of the Anti-Corruption Foundation. In the case of Agora, authorities justified their actions by stating that the human rights defenders were assisting “opposition figures with outwardly anti-Russian views”.

In a single year, 50 names were introduced into the list of “undesirable” organizations. Among them were the online media outlet Meduza, non-governmental organization Transparency International, Greenpeace, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), Novaya Gazeta Europe, the Free Buryatia Foundation, the Central European University, and others. All these organizations supposedly pose a threat to the foundations of the Russian constitutional order, the country’s defense capabilities, or state security. Some of them had also previously been labeled “foreign agents”.

Aside from the restrictions imposed upon the organizations and their members, the law also bans ordinary Russians from participating in the activities of such organizations (including disseminating materials produced by them), as well as providing and collecting funds or offering any kind of financial services. Violation of these bans would result in administrative and criminal liability.

The Wagner Group – from adoration to oblivion

Also in June, following Evgeny Prigozhin’s rebellion and the Wagner Group’s march on Moscow, authorities quickly changed their official rhetoric. This was despite a law being passed, just a couple of months previously at Prigozhin’s urging, which imposed 15-year sentences for spreading fake news about any participants in the special military operation, effectively prohibiting Russians from speaking out against the “Wagnerites” (see March).

On central TV channels and pro-Kremlin Internet media platforms, Prigozhin and Wagner Group members were labeled as traitors, with Vladimir Putin calling their actions “treason” and a “stab in the back”. Literally the next day, on June 24, the “unspecified government agency” added a site recruiting “volunteers” to the Wagner Group into the Unified Register of prohibited information, and then a few days after that, another of their sites: “Wagner PMC – Soldiers of Fortune”.

Their messages and even social media groups were deleted. A website which publishes official laws removed the page outlining laws on “discrediting” volunteers. Everything that was previously deemed socially beneficial and approved by the upper echelons of government was swiftly prohibited.

What happened next

July

“Foreign agents” and their “third parties”

In the summer, “foreign agents” encountered heightened challenges as legislation governing them became more rigorous. The legal framework was used to block websites without clear justification, and the lists of designated “foreign agents” underwent active expansion.

A pivotal addition to the legal landscape was the introduction of “third parties,” individuals or entities aiding those recognized as “foreign agents.” The Ministry of Justice was granted authority for unscheduled inspections of these third parties. Stringent penalties for non-compliance with Ministry directives were imposed on “foreign agents,” including restrictions on political activities, election observation, event organization, and educational initiatives. These laws, signed by President Putin in July 2023, underscored a significant shift in the regulatory environment.

Preceding this, the Ministry of Justice initiated abrupt website blocks targeting “foreign agents” without lawful grounds. Notable additions to the list included websites associated with the OVD-Info project, Ukrainian journalist Dmitry Gordon, and entrepreneur Dmitry Davydov’s “20 Ideas” project.

The comprehensive list of “foreign agents” witnessed a substantial increase in 2023. As of December 1, it encompasses 728 individuals and organizations, with 213 additions this year alone. This diverse group spans journalists, independent media, activists, NGOs, musicians, artists, politicians, and former deputies.

Technological Sovereignty and National Internet Resilience

On the night of July 4-5, 2023, Russia reportedly “shut down the international internet” to assess the resilience of the Russian segment, as part of the “sovereign RuNet” law. These exercises, conducted at least six times since the law’s enactment, aim to test the ability of the Russian internet to function autonomously. Despite the legal requirement for a published schedule within five days of approval, no such schedule for internet shutdowns has been released this year, and past schedules have often been disregarded. The domestic internet influence extends beyond infrastructure, as the Russian store RuStore is mandated to pre-install on all devices imported into the country, even if the OS rights holder objects, potentially requiring unpacking. Additionally, manufacturers must ensure that the domestic app store is displayed on smartphone screens just like programs from other developers. For now, buyers of new iPhones need not worry, as RuStore is currently available only for Android.

What happened next

August

Digital Transformation of the Ruble

August marked a significant milestone as the Russian Ruble transitioned into the digital realm. The law introducing the digital ruble was enacted and signed in July of this year, with its key provisions taking effect on August 1. Midway through the month, real operations with the digital ruble commenced, accompanied by inquiries from the Association of Russian Banks (ARB) seeking clarification from the Central Bank. The ARB sought to understand the nature of the digital ruble, the mandatory participation in the experiment, and the procedures for fund withdrawal.

Thirteen banks, including VTB, Alfa-Bank, “DomRF,” Ingosstrakh-Bank, Gazprombank, Kiwi-Bank, “Ak Bars,” MTS Bank, Promsvyazbank, Sovcombank, “Sinara,” Rosbank, and TKB, along with 30 retail points and approximately 600 citizens, including Moscow Metro employees, participated in the pilot project. Initial stages involved the opening of wallets and testing transfers between them. In October, the Moscow Metro joined the trial, allowing the purchase of the “Troika” travel card with digital rubles.

The testing phase of this “third form” of currency is anticipated to continue into 2024, with full-scale implementation slated to begin in 2025. Questions surrounding the digital ruble persist, and answers will be incorporated into documentation as they arise.

Operators Left without 5G

In an unforeseen development in August, the frequency range most suitable for deploying 5G will be allocated to law enforcement agencies. These agencies will gain full control over communication networks, including the authority to disconnect civilian networks during emergencies. This revelation is outlined in the updated strategic plan for the development of the Russian telecommunications industry until 2035, presented in August.

Telecommunication operators had initially anticipated acquiring frequencies in the 3.4-3.8 GHz range for 5G network development. However, the new document indicates a prohibition on their use for civilian purposes, as these frequencies are currently occupied by equipment for the Ministry of Defense and the Federal Security Service (FSO).

The implementation of the new strategy will occur in two phases, from 2023 to 2030 and from 2031 to 2035. Specific mechanisms and changes will unfold as surprises for us in the future.

What happened next

September

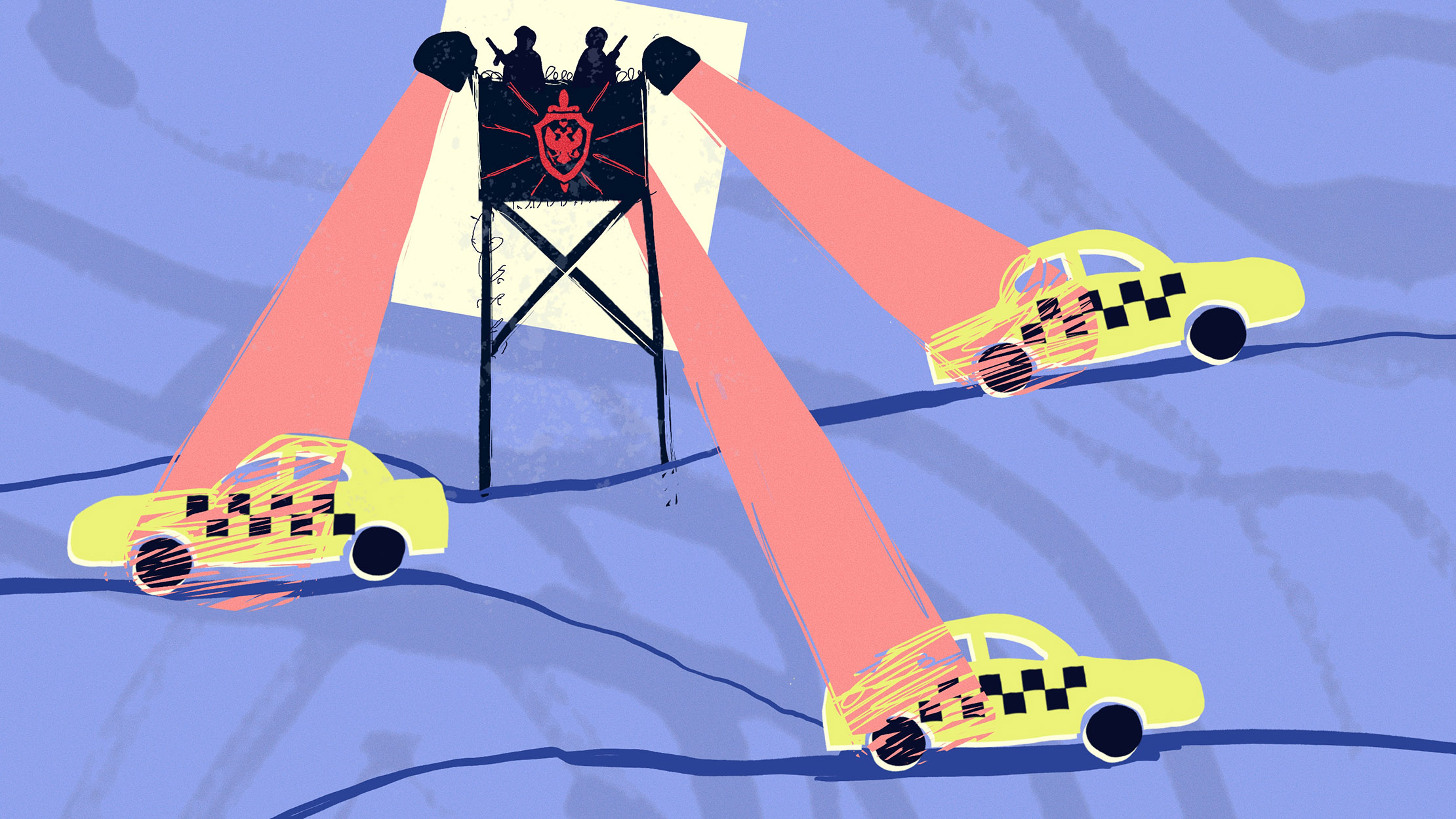

FSB Enters the Realm of Ride-Sharing

A paradigm shift occurred in the ride-sharing landscape in September. As of September 1, 2023, taxi services were mandated to provide the Federal Security Bureau (FSB) with comprehensive data on all passenger trips. “Round-the-clock remote access” was granted to law enforcement agencies for databases used in receiving, storing, processing, and transmitting order-related information. This access extends to applications used by both passengers and drivers. Previously, obtaining such data required legal procedures, but the new law streamlines the process. Additionally, drivers are now prohibited from working with outstanding convictions and unpaid fines.

While the FSB likely possesses geolocation data, payment details, and trip dates/routes, passenger identification is restricted to phone numbers. This, however, introduces potential risks of data confidentiality breaches. Nevertheless, ride data can supposedly be permanently deleted, as asserted by services like Yandex.Taxi support. Instructions on how to achieve this are provided.

Spyware Pegasus Unleashed

In September, a new scandal unfolded involving the spyware Pegasus. The software was discovered on the iPhone of Galina Timchenko, the CEO of “Meduza.” Pegasus gains access to all phone contents, including contact lists, the internal microphone, and the camera.

Researchers from Access Now and Citizen Lab found that Timchenko’s phone was infected two weeks after “Meduza” was declared an undesirable organization. Experts speculate that, in addition to Russia, allied countries like Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, or Azerbaijan could have implemented surveillance. EU countries—Germany, Estonia, and Latvia—where the publication has offices, also came under suspicion. Resisting Pegasus installation is nearly impossible; any vulnerable app on a device can be exploited, including those native to Apple.

Timchenko became the first Russian journalist attacked with Pegasus. Previously, researchers discovered a list of 50,000 numbers monitored by Pegasus’s developer, NSO Group. The list included 85 activists, 189 journalists worldwide, and numbers of several heads of states and prime ministers. In 2023, The Citizen Lab identified a Pegasus analog—QuaDream—also used for tracking journalists and opposition figures.

State Ownership of Biometrics

In a significant development, Russian citizens’ biometric data became state property. Banks began notifying clients who had previously submitted biometrics about the transfer of their data to the Unified Biometric System (UBS) starting in June. The law governing the UBS, signed and accepted at the end of the previous year, required this transition by September 30, involving the transfer of up to 75 million facial images to the government.

Originally perceived as a voluntary process, individuals were expected to have the right to refuse data transfer. However, Tinkoff Bank took an assertive stance, seeking consent to convert product-related photos (taken during card delivery) into biometrics, sparking widespread criticism. If you hadn’t provided biometrics to banks or consented to data transfer when asked, there’s no need to worry. If you prefer the state not to use your biometric data, refusal can be communicated through the MFC. In September, MFCs experienced an overwhelming demand for this service, but it’s never too late.

What happened next

October

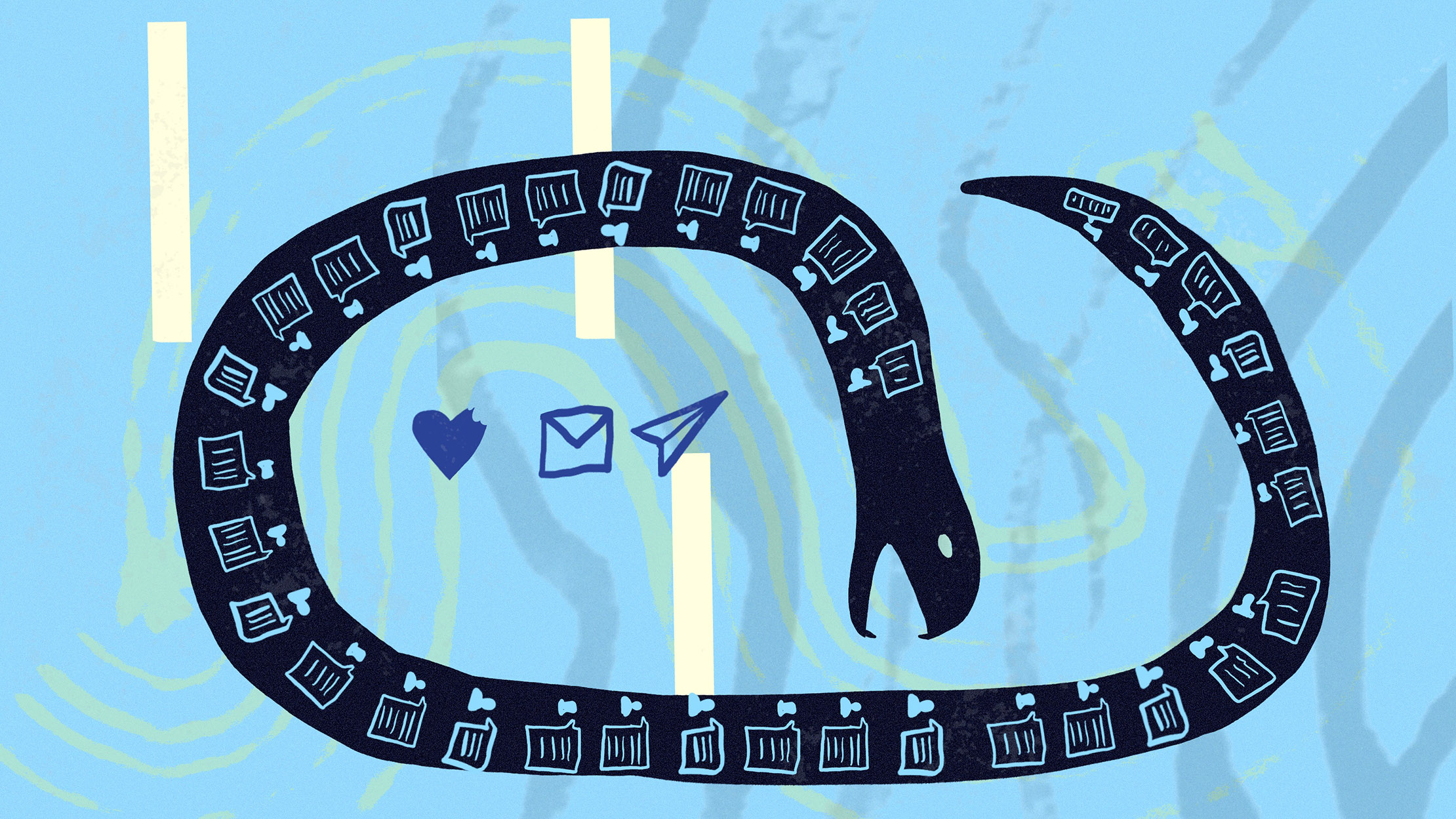

Expansion of Surveillance Registry

By October, the Surveillance Registry (ORI) experienced an influx of over twenty diverse companies. Among them were major Russian services such as “Aeroflot,” “Ostrovok,” “Kassy.Ru,” as well as foreign entities like Mega, PUBG, MediaFire, BigoTV, and others. The law mandates all services listed in this registry to collect, store, and provide Russian security services, upon their first demand, with comprehensive user information and interactions on the platforms. This includes internal messaging, calls, file exchanges, geolocation, orders of goods and services, etc. The registry’s growth and data storage requirements are explained under the pretext of combating crime and terrorism. Special attention is now given to authorities who can easily determine your flight details, hotel stays, and preferred concerts.

Concerning foreign companies, it remains unclear whether they comply with Russian legislation. “Roskomsvoboda” queried these companies about notifications from Russian authorities regarding inclusion in the ORI registry, clarity on the consequences, and any public response. As of writing, no responses have been received. Here, we provide a detailed explanation of which companies enter the registry, its structure, and the consequences if user data is not stored or transmitted to authorities.

Ban on “Pornofilmy” and Musical Censorship

Punk rock and rap are gradually becoming prohibited genres in Russia. Individual compositions and entire albums are deemed extremist, added to the list of banned materials, removed from Russian music platforms, and even have song lyrics and chords prohibited.

In October, the authorities paid particular attention to the creative works of the punk group “Pornofilmy.” Several links to the lyrics and chords of their song “Eto Proydyot” were added to the registry of banned sites by an “Unspecified government agency.” Later, this same song was removed from VK and “Yandex.Music.” A similar fate befell the song “Rodi Mne 1000 Detey,” which is now also unavailable on Russian services.

However, this is not the first act of censorship against “Pornofilmy.” Another song, “Kill the Brokes!,” was twice deemed extremist in Russia, with its lyrics included in the list of banned materials, but decisions were made by regional courts. The group’s vocalist, Vladimir Kotlyarov, was also included in the registry of “foreign agents” this year.

The authorities also disapproved of the works of rappers, including Oxxxymiron and “Ligalayz.” Oxxxymiron’s track “Oyda,” where the prosecutor’s office found “public positive attitude toward the separation of part of the territory of the Russian Federation expressed in the form of a slogan,” was outright banned by a court decision in St. Petersburg. The track “Posledniy Zvonok” was previously declared extremist in Russia by a lawsuit from the Moscow prosecutor’s office. Both compositions regularly contribute to the list of banned sites. Oxxxymiron himself has been recognized as a foreign agent and fined multiple times for calls to separatism and “discrediting the army.”

A link to the music video of the rappers “Ligalayz” (D.O.B.) & Mr. Freeman’s “Mir!! Vashemu!! Domu!!” was also blocked by an “Unspecified government agency” (likely the General Prosecutor’s Office for military censorship). Ligalayz himself was investigated by the prosecutor’s office for discrediting the army after his statements in an interview with Yury Dud.

A prominent opponent of musicians is the “League of Safe Internet,” known for its informants. Journalists counted that its leader, Yekaterina Mizulina, complained about at least 166 people, mostly musicians and bloggers, and four musical groups. Fourteen of them faced fines under various articles, criminal cases were initiated against four, and at least five encountered concert cancellations.

What happened next

November

Government Interest in Users

Russian authorities have increased their requests to internet services, seeking content removal or information about specific users. Services, in turn, openly disclose the number of such requests in their transparency reports.

In November, “Yandex.Music” published its inaugural report. Since the beginning of 2023, the service removed over 4,000 materials due to reasons such as “fake news about special operations,” “discrediting” the army, LGBT themes, suicide, extremist content, disrespect for the state, and drugs. “Yandex” itself, in the first half of the year, removed over 190,000 links from search results at the request of Roskomnadzor.

Google received over 36,000 content removal requests from authorities in the first half of 2023 (the highest globally, with 58% related to national security). Russia also ranked 3rd out of 30 for the number of videos removed from YouTube for violating community standards (571,000 videos).

For the first half of 2023, Russian authorities approached Microsoft 477 times for content removal, with the company taking action on 319 of these requests. Meta received only one request during the same period, likely due to the organization being declared extremist in Russia. Reddit faced 22 requests from Russian authorities, mostly related to political expressions and “special operations.” Additionally, Pikabu received 150 removal requests and 14 notifications of monitoring from Roskomnadzor in the third quarter of 2023. Pikabu is the second Russian internet resource, after Habr, to regularly publish transparency reports, a practice also adopted by “Yandex.”

Foreigners’ Loyalty

Foreigners in Russia may face restrictions on criticizing the government. The Ministry of Internal Affairs proposed requiring incoming foreigners to sign a “loyalty agreement.” It entails a prohibition on discrediting the country’s external and internal policies, as well as limiting the right to freedom of information.

It is anticipated that foreigners will need permission from Russian authorities for entry, and before entering, they must agree to “comply with prohibitions aimed at protecting the country’s national interests.” They will also be prohibited from “promoting LGBT” and distorting the history of the Great Patriotic War. The project is currently being developed collaboratively by the State Duma Committee on CIS Affairs, the President’s Administration, the Russian government, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs. By the time the new rules are adopted, the number of restrictions may significantly increase.

What happened next

December

Fines for Social Media and IT Companies

Fines incurred by social media and foreign IT companies marked the year, encompassing platforms, including those blocked in Russia. These penalties were attributed to various infringements of Russian legislation, such as non-compliance with landing laws, failure to remove prohibited or false information about the army, failure to localize data, and violations of the law on self-censorship.

The law on self-censorship for social media became effective on February 1, 2021, with amendments to the Code of Administrative Offenses scheduled for implementation on September 1, 2023. This legislation designates internet resources with daily traffic exceeding 500 thousand users as social networks, requiring them to be listed in a dedicated register. These platforms are tasked with independently identifying and restricting access to content deemed illegal, along with an annual publication of a report on their efforts and the establishment of a user contact form. Since September, 14 protocols have been established under this law, with six undergoing court review. Fines ranging from 750 to 900 thousand rubles were imposed on Pinterest, Twitch, Google, TikTok, Telegram, and Likee.

Eleven additional services faced protocols for non-compliance with landing laws, obliging large foreign IT companies with a daily Russian audience of 500 thousand people to establish representative offices, register on the Roskomnadzor website, and incorporate an electronic feedback form for Russian citizens or organizations on their platforms. Failure to adhere to these requirements could result in various “coercive measures,” including potential blocking in Russia. Presently, 26 foreign companies are listed for “landing.”

Google incurred the largest fines in Russia, reaching 4.6 billion rubles in December 2023 for repeated failure to remove prohibited information, including false details about a special operation and LGBT content. In October, Google’s Russian subsidiary, Google LLC, faced bankruptcy in Russia.

Several other foreign companies received fines in recent months for refusing to localize Russian data, with PUBG Mobile (1 million rubles), Tinder (10 million rubles), and Twitch (13 million rubles) among those penalized. The companies’ awareness of these fines and their intentions to fulfill payment obligations remain uncertain.

Closure of Wikimedia and Import Substitution of Wikipedia

The organization “Wikimedia RU,” responsible for supporting the functioning of Wikipedia in Russia, has officially announced its closure. Executive Director Stanislav Kozlovsky made this announcement after facing dismissal from Moscow State University (MSU) following nearly 25 years of service as an associate professor in the psychology department. The decision was prompted by information received by the dean’s office, indicating that he would be declared a “foreign agent” the following Friday.

Kozlovsky emphasized that the closure of the organization supporting Wikipedia’s operations does not imply the shutdown of the encyclopedia itself. If it is not blocked in the Russian Federation, it will continue to operate, as there are enthusiasts contributing articles. At present, Kozlovsky has not been officially designated as a “foreign agent,” possibly due to public outcry.

In April, the head of the Presidential Council for Human Rights, Valery Fadeev, expressed opinions about the potential closure of the Russian Wikipedia, while Deputy Anton Gorelkin hinted at possible delays. By that time, more than a hundred articles had already been banned on the Russian Wikipedia.

By June, a domestic alternative to Wikipedia emerged in Russia – the “RuWiki” website, followed by another analogue a few months later, the encyclopedia “Runiversalis.” Authorities proudly stated that the new “Wikipedia” declared a respectful attitude towards the legal requirements of the Russian Federation and our traditional values.

Our newsletter

The main news of the week in the field of law.

Contacts

18+

On December 23, 2022, the Ministry of Justice included Roskomsvoboda in the register of unregistered public associations performing the functions of a foreign agent. We disagree with this decision and are appealing it in court.